Discount Points, or simply points, are an upfront fee charged OR credit received by the lender to change the interest rate on a mortgage. They act as a granularity tool to measure risk appropriately without unfairly changing the rate. Paying extra at closing for a lower rate is called a “buydown”, while receiving a credit to closing costs in exchange for a higher rate is called a “buy-up”.

Key Takeaways:

One point = 1% of the loan amt. 1pt on a 250k loan = $2,500. The same 1pt cost on a 500k loan is double = $5,000.

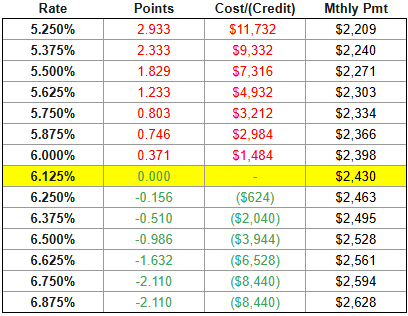

A quoted rate is actually a menu of options, and each rate has it’s own price.

The rate with a ‘price’ closest to zero is called the “par” rate.

There's no fixed formula for how much each point lowers your rate—lenders reset their “menu” daily based on their needs and market conditions.

Paying points to lower your rate is called a "buydown"; accepting a higher rate for lender credits is called a "buy-up"

The difference in the menu prices are NOT linear.

There is NO set formula for how lenders determine their menu’s prices. These prices are reset daily and are based on the lender’s own business needs.

The rate in this menu with a cost/credit closest to zero (highlighted above) is called ‘par’. Unless you’ve been roped into an enticing online advertising campaign, this is normally the rate you get quoted.

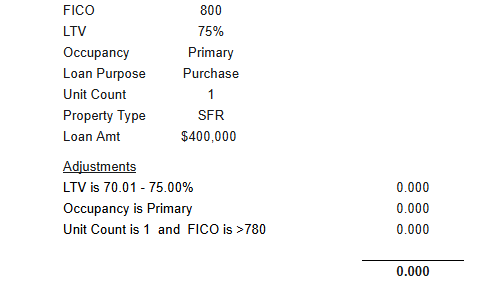

Rate sheets are influenced by risk adjustments.

Consider a bank who wants to offer mortgage loans. They’ll start by identifying market rates for the cookie-cutter mortgage scenario, create their own rate sheet, and when someone walks in that day looking for a loan on something that isn’t cookie-cutter, they add those adjustments to their original rate sheet.

For instance, let’s assume the table above is, in fact, the “cookie-cutter” scenario. It’s criteria might look like this:

EXAMPLE 1:

Using the rate table above, you could add an extra $2,369 to your closing costs in order to lower your rate from 6.125% to 5.750%; thus lowering your mthly pmt by $70.

*Excluding the effects on equity, interest, and taxes, this means you’d make that $2,369 back in 34mo. So, if you’re certain you’ll stay in that loan for >34mo, then that might be a good option.

Points work as the granularity tool—a way to align price and risk even when it doesn’t fit in neat 0.125% boxes.

There’s no fixed conversion between points and rate cuts: that ratio moves daily, lender by lender.

Generally, however, the further a rate choice moves from the “par” rate (no points attached), the less beneficial it typically becomes for the borrower.

As we just learned, deviations from the cookie-cutter scenario increase risk and thus, rate. But not all risks are equal, and most aren’t enough to change the rate an entire eighth.

Wiki Link Hex Code Color: #85B2E1

Terminology Page. Subpage of wiki.

When you’re quoted a mortgage rate, your loan officer will likely give you a single rate. In reality, you’re actually getting a menu of options called a “rate stack”. This list of rates, organized in 0.125% interest rate increments, will have their own associated cost or credit (read: “points”).

Here’s what that looks like: